Ann Marie Davis, PhD

How Are You Teaching?

Virtual Labs for Teaching and Learning about East Asia

Dr. Ann Marie Davis is an assistant professor and Japanese Studies librarian(link is external). Prior to joining Ohio State, she was a history professor at Connecticut College where she taught courses on Japanese history, East Asian empire and expansion, and the history of women and gender in modern Japan. She earned a masters degree in Regional Studies-East Asia at Harvard University; a PhD in Japanese History at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA); and a masters in Library Science at Southern Connecticut State University. Her recent book manuscript, Imagining Prostitution in Modern Japan, 1850–1913, was published by Lexington Books in 2019.

In the past year, she has transformed her teaching to address the COVID-19 pandemic, including her approach to online, hybrid or socially-distanced classroom teaching, and racial and social justice.

My Teaching Strategy

Emphasizing an interactive learning environment that models exploration through experiential, project-based and collaborative learning. Teaching that fosters community, connectedness and engaged learning through remote delivery.

Inspiration

We were inspired by the strong community building and networking that our annual summer seminar for K-12 teachers (on teaching about East Asia) has fostered in years past. Formerly held in person, our one-week course has always emphasized a supportive and collaborative learning environment. With the unexpected pivot to remote delivery, we were looking for ways to continue and expand our community building online despite our geographical separation. Additionally, we wanted to explore online pedagogical opportunities and strategies that our teacher participants could use in the fall as they faced similar challenges adapting to remote delivery.

In Practice

To build greater connectedness, we focused on student-centered, experiential and collaborative lessons. We intentionally grouped the participants based on teaching specializations, levels of experience and grade levels. To create a type of virtual learning lab, we mailed pedagogical materials to the participants in advance, who, in turn, explored and studied the materials before and during class.

In our unit on tea, for example, we sent five different samples to five different groups respectively. During the lecture, the groups were sent to breakout rooms to brew, smell, taste, and discuss the properties of their respective teas. Similarly, for our unit on paper-folding, students received origami paper by mail. During the lecture, they went into breakout rooms to practice folding specific origami objects and discuss. Like with the tea exercise, this activity emphasized interactive, hands-on learning in small group settings.

Following this model, we also implemented a scaffolded, project-based assignment in the form of a final book report. Interim assignments incorporated technologies like FlipGrid, which encouraged participants to engage one another asynchronously while learning technological tools that were needed for the book project. Before the first day of class, participants posted short self-introductions on FlipGrid for asynchronous viewing. Meanwhile, they selected their books and were placed in book groups.

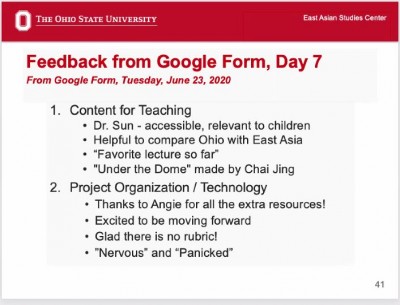

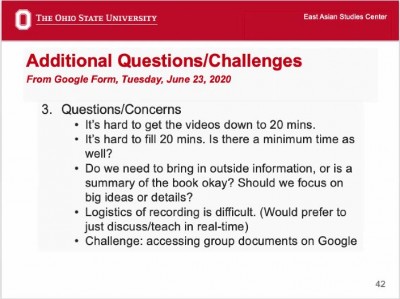

Once the seminar was under way, the groups met daily to plan and ultimately record their reports on FlipGrid. During their daily breakout sessions, group representatives completed a Google form that shared anonymous feedback, reactions and questions. These online forms became vital communication tools that fostered an even greater sense of connectedness with the entire class. Through these forms, seminar leaders could better track participant experiences, recognize potential themes, and report back to the class on exciting ideas and potential concerns.

Student Response

“.I was worried that this might not be a personal experience...You did an AMAZING job making this seminar personal and getting everyone actively involved...You really can't put into words how powerful the experience was..."

“My first main takeaway from this seminar is that virtual learning can be done successfully and collaboratively. People can work together and participate even when they are not in the same room. This gives me hope, because school may look like this in the fall...My teaching is forever changed and my students will reap the benefits…”

“The format of this workshop itself has set up a great model for me to plan for my possible future online class if that is what the situation requires. I was at my wits' end when I started to deliver my lessons online in March...”

Advice to Other Instructors

Be open to the opportunities created by the remote learning environment rather than focusing on the challenges. Find ways to build community through shared experiences (e.g., hands-on activities and collaborative projects) while creating flexibility with asynchronous tools. Identify the advantages of online teaching, such as the ability to expand the geographic scope of the participants and guest speakers. (In our case, we included teachers from several nearby states and hosted guest lecturers from as far as South Korea). As a result, our 2020 COVID-19 cohort of 23 teachers from six states will impact over 4,000 students this year.

Additional Resources